This site in German

|

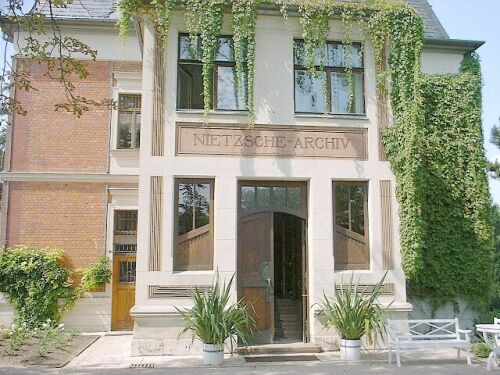

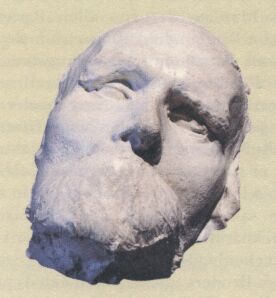

Nietzsche's Death and the Memorial Gathering at the Nietzsche Archive  The Nietzsche Archive in Weimar Photo: H. Walther (2000) (Source: Das Nietzsche-Archiv in Weimar, Carl Hanser Verlag München Wien 2000, p. 47--An English description of the content of the preface and a translation of Horneffer's Speech held in 1900) The preface of the above-noted book briefly mentions Nietzsche's death and his illness leading up to it, namely a fever he contracted on August 20, 1900, which is reported as soon having attacked his lungs. He is further reported as having suffered from a strok in the night of August 24 to August 25, 1900, and as having passed away during the following morning, between 11 and 12 o'clock, on August 25, 1900. During his illness, Nietzsche is reported as having stayed in his bedroom on the second floor of the 'Villa Silberblick' and as having passed away 11 years after his break-down in Turin, Italy. His sister is reported as having prevented an autopsy of his remains and as having announced that Nietzsche had died from chloral hydrate (a sleeping medication) poisoning. Elisabeth is reported as having wished for the already renowned scuptor, painter and graphic artist, Max Klinger, to take her brother's death mask. However, at that time, Klinger is reported as having stayed in Paris, so that the task had to be entrusted to Curt Stoeving and Count Harry Kessler, who performed this task in the morning of August 27, 1900. Even though their inexperience is reported as having caused Nietzsche's face to show irregularities cause by his partial facial paralysis, the mask they took is reported as having later served Klinger and various other artists as a model for their Nietzsche portraits. Nietzsche's sister Elisabeth is reported as having invited a 'close circle' of friends and acquaintances for a memorial gathering at the Villa Silberblick. The approximately twenty guest thus had to file into the small library room that was decorated with flowers and wreaths, while candles were burning at Nietzsche's open coffin. The architect Fritz Schumacher reported that the Berlin historian Kurt Breysig was 'mercilessly reading a cultural-historical analysis of the phenomenon Nietzsche.' Two lady friends of Elisabeth, Freifrau von Thüna and Fräulein von Prott rendered an a capella performance of Johannes Brahms' Wenn ein müder Leib begraben to verses by Klaus Groth and of the elegy by Palestrina, Qua fremuerunt gentes; in-between, the Nietzsche editor, Ernst Horneffer, as Kessler reported, held a speech, 'with tact and fire.' Elisabeth's wish to obtain permission to have her brother buried in the back yard of the 'Villa Silberblick' and Nietzsche Archive was not granted. Rather, Nietzsche's remains were transferred for their burial in the Nietzsche family plot at Roecken on August 28, 1900.  Library Room at the Nietzsche Archive in Weimar, designed by H. van der Velde (1903) Photo: H. Walther (2000)  Library Room at the Nietzsche Archive, opposite side Photo: H. Walther (2000) Speech held at Nietzsche's Coffin on the occasion of the memorial gathering at the Nietzsche Archive in Weimar on August 27, 1900. Dr. Ernst Horneffer, Nietzsche-Vorträge, Many voices will be heard at Nietzsche's grave, for the hour has arrived in which his word has reached even the remotest listeners where every soul resounds in some way. And thus they will let their voices be heard on this occasion in one way or another. When I am asked to speak in this silent, serious house, in which this great one slowly perished, when I am asked to speak a word by those who were nearest to him, then I can only do it in such a way that I share my own emotions of the moment. Only in this way is it the way that he who passed away would have approved of it. Thus, I can not fail that my words will express the mood and the emotions of a certain youth of the day, of a certain link in the chain of generations. And what is more, they will also express my most personal feelings that I can not deny in this moment if I want that what I say does not lack color and meaning. And thus, following my feelings, with the truth that this holy hour presents as my duty to me, I say: at the grave of this man, any mourning is forbidden. May those who were near to him from his early youth on by way of kinship or by way of friendship ties, may they, in memory of his lively image, an image full of secrets, tenderness, of solemn beauty and of noble greatness, give expression to their pain. We honor this pain. They ultimately lose something incredible, something, the value of which can not be measured by anyone of us who is not part of their circle. However, we, who did not have the opportunity to get to know him as a man, but who have come so close to him, up to the threshold -- at this threshold, however, we are confronted with the impossibility -- we, who can only grasp his intellectual legacy, we may not mourn. All mourning can easily turn into complaint and regret, and who are we that we would be allowed to voice regrets with respect to this life! O no, this man forbids us to show our compassion! every compassion that we small, short-lived people of this day can offer this life, will make us despicable. This man is too proud that he would want anyone to show him compassion. After all, he is the great protagonist who also accepts his own life and would not want to have changed it, not in retrospect, not in future, not in all eternity. And in the face of this we should mourn and show compassion? Let us take a look at his life. Very early, against all expectations, he is recognized as of rare importance. Against all tradition, he is endowed with positions of esteem, even before he has completed his preparation for them. One did not wait until he applied for such position(s), one offers them to him out of one's own accord. And his first writings have impact. His circle of friend surround the young thinker who, already here, speaks like a prophet, in agreement, nay, in jubilation. And more than that: fate leads him to that great artist the image of which was surrounded by controversy then and now but whom one can not deny that he is a great artist and will never be able to deny it. I believe that Nietzsche would have wanted the name of Richard Wagner mentioned here. Through his relationship, a peculiar glamour surrounded his early years. Through it, he learned to revere someone from the bottom of his heart, something that he, in his later life, would have to unlearn. What an emotion for the one who, in his later life, would have nothing left to revere, since he felt everything as being beneath him! Yet, everything turned out quite differently. His great official career which one foresaw after his first successes, it could not be realized. And his friends were alienated from him, one by one. However, who should have been able to follow him when he went his own path? However, the decisive break was this, the break-up of his relationship with Richard Wagner. With it, he became the great lonely one. However, I ask you: was this sacrifice not necessary? How should he have found the freedom to embark on his work -- and no work required greater freedom! -- if he would not have broken this bridge behind him? Thus, from that moment on, we see him lead the life of an unsteady wanderer that led him to the highest mountain peaks and to the remains of an old culture. A peculiar image how he thus, even the last shackle removed from him, surrounded by a sea of freedom, created his work. It is hardly imaginable, in the suppressed, narrow confines of our days, this over-abundance of freedom! He lived like a royal, splendid hermit of the mind, such as our times, in his opinion, completely lacked. For all times, his life serves as the great school of independence. And what did he turn in during this time? He became the most searching, most investigative, most thoroughly digging mind that ventured into the deepest crevices; and he became the most active mind in whose work not only sparks and splinters flew about, nay, also great blocks and chunks; he turned into the most sensitive mind that felt the slightest trembling of the human soul, sensed it and expressed it in our heavy language, and above all: he became the genius of the heart that paralyses every resistance, the great wizard and magician to all, to whom everyone who has heard his voice once, will be beholden. And thus he created work after work. Ever higher did he climb, ever more hurriedly, up to the highest peak, where he was just about to take his last, great look around -- when he was struck by lightning. However, when one admires and blesses this proud life, one might, perhaps, view his sudden break-down at the decisive hour as something that should be eternally mourned and regretted. I understand this very well, and yet, I ask here: would one even want to have more? First, we did not want to accept his treasurers, and now, we can not get enough of them. I think that this man dug gold, poured out gold, enough to satisfy every craving. Perhaps this is why I who is fortunate enough to work with his writings, hold this opinion. If one looks at the entire wealth of his body of work and to what extent some of his works, particularly in the last years, were in everyone's hands, and also that they are only bits and pieces of his entire body of work, then one asks oneself: could more even have been possible? And finally this death. Nietzsche once asked himself if he would perish in a storm or if he would go out like a light. Both has been fulfilled. First, he perished in a storm, and then he went out like a light. This two-fold death can, if one wants, have a meaning. Nietzsche was able to make do without mankind; the question is only if mankind can make do without Nietzsche. It is as if Nietzsche, with the kind of death that he died, wanted to invoke a terrible punishment. Just when he had reached his last peak, when it would not take much longer that he would be recognized, he vanished, but not entirely! A remainder of him was left behind, enough, to teach us what we had missed! We still saw him, his noble head, full of royal pride, from which his hair flowed softly and fully, as if, from the origins of mankind, a sage had reappeared. Thus, the more he languished, he awakened longing after longing, and grew all the livelier. This can be said of this death: one should mourn the dead and not the living. This man who is lying in this coffin here, he is not dead; we who are surrounding him, we are shadows, mere death-like shadows compared to the abundant life that blossoms in this coffin. There has never been a more lively dead corpse! And this victorious thought, I believe, could even bring comfort to the heart of she who is suffering the greatest pain, into the heart of his sister, whose life was entirely dedicated to taking care of the deceased. It is not night that is breaking out with the death of this man, as with the death of other men; it is a morning, a new day. We shall yet experience and see an infinite number of dawns. How everything will appear bathed in their light! Do we not feel it? I believe to see how the dead man is rising, how he is getting up -- and to his feet, a world is crumbling. If is not as if we would believe that we could already understand his worth, today. We have no knowledge of him. It is as if we were standing at a seashore; the waves are lapping at us, we can hear them with our ears, but we can not fathom the vastness of this sea. We only know that Nietzsche is arriving, that he is coming closer and closer, that he is rising higher and higher; there is no escape: Nietzsche is growing. Do we not hear the spirits that he sent out and that are hovering above us in the air? They are close, the dangerous, the sinister, yet refreshig and strengthening tides that he prophesied. Let us wait -- only for a while, and all old ice will melt. We are not mourning at this coffin. It is not as if we did not know that this life was a life of utmost suffering, yet, I dare to say that this man who brought the highest happiness that an entire mankind can not fathom, himself, was certainly the most unhappy man who ever walked the earth. He knew pain as no man has ever known it, bodily pain and pain of the soul, as if fate wanted to revenge itself on him, revenge itself on him for all joy that would go out from him, as if it would only have granted him to pour out his joy for this price. We know that everything that Nietzsche accomplished, he accomplished "in spite". -- When we leaf through his writings here at night, and if we come across one of his letters to a friend of his youth, out of his loneliness, out of his cave, in which he asks his friend to pat his children on their heads in his name, and when he, so-to-say, in foreboding of his fate bemoans his fate and calls out, woe! what if? what if he would, at some time, not be able to bear this loneliness, anymore! thus we would need music as Saul did, in order to keep himself going; fortunately, fate also put a faithful David at his side -- there are tunes in Nietzsche that even break the hardest heart. And yet! The searching for the most sinister, most questionable aspects of life without trembling, that is what Nietzsche teaches us, acceptance of even the strangest, most inexplicable fate! Well, then! Let us prove Nietzsche's teachings, first and above all, here and now, in the face of his death! Here, there is a strange fate. Here, in front of us, in this coffin, lies Friedrich Nietzsche who had ventured out in order to return, who still had wanted to spread his own teachings, who had pleaded with his fate: save me for a great victory. Let us fully keep this in mind -- yet let us not mourn. The representatives of mankind visit Zarathustra in order to tempt him; they want to tempt him to give in to his last sin, to have compassion with the higher man. Is it not as if the leaf has turned and as if Nietzsche is now visiting mankind, as if he, with his life and with his fate, wants to tempt mankind, as if he wants to tempt it to commit its last sin, to show compassion with the highest man? That his fate, that the pain of his fate is thus, that in its face, if it is spread from generation to generation, ultimately, all of mankind could break, I do not doubt. There has never been anything more tragic in all of mankind's history. Nietzsche's life and fate will forever remain the standard by which his teachings are judged. And just for that, let us move on! Let us withstand! The great noon will never come when we do not overcome this first challenge -- and after us all generations. I know, my speech sounds peculiar. However, only then will his work not have been laid before us in vain, when we embark on meeting this challenge. As expression of my gratitude, as my vow for now and for the future, I call out these words over the grave of Friedrich Nietzsche, who has met the most untimely death of all: amor fati! »Höchstes Gestirn des Seins! Schild der Notwendigkeit! Schild der Notwendigkeit!  Nietzsche's Death Mask |

You are visitor no. .

since January 22, 2002. My thanks for this counter go to http://www.digits.com/