This site in German

At my partner site, you will find an already very well-developed compilation of Friedrich Nietzsche's works, which you can read up in German there:

This site's chronological listing of Nietzsche's works and the fragments of estate are not only available in full text, but you can also search certain passages in these works. Here the respective links:

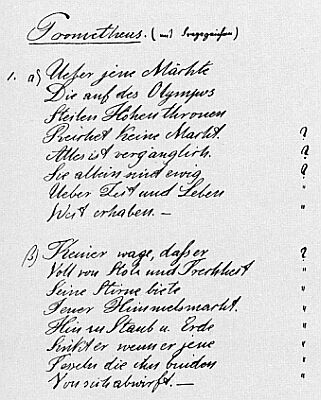

Selected Texts from Nietzsche's Early Works Of course, you should also have an opportunity to become familiar with excerpts from Nietzsche's work ere, namely mostly with those that are not as easily accessible, meaning text that are contained in the so-called BAW (Beck's Edition of Works) edition. This edition was a first attempt of a histirocal and critical edition of Nietzsche's works that was started in the 1930's and as mainly prepared by Hans Joachim Mette. After the publication of five volumes, this edition was not continued, due to the outbreak of World War II. It contains Nietzsche's youth works from the years 1854 - 1869. From these, I want to present those that appear particularly important to me with respect to the development of the philosopher in NIetzsche. At the same time, I want to present some of Nietzsche's letters of this period which are contained in Volume I, 1850 - 1865 of this historical and critical edition, since I agree with Professor Dr. H. J. Schmidt, Dortmund, Nietzsche absconditus, see the Listing of Literature) insofar as he maintains that a thinking such as that of Nietzsche does not appear all of as sudden as in his work The Birth of Tragedy, his first book publication, but rather that thee have to have existed pre-development stages--which did, actually exist. This is my particular focus here. You can find two early and important poems of 1858 (Zwei Lerchen und Colombo) on document page III of the section on Lou Salome III; here, I want to feature the, in my opinion, earliest text in which he deals with his own viewpoints in an undoubtedly reflective manner and even renders a satire (from his "Prometheus" BAW I, p. 62 - 69). He literally plays with those passages in his text that are of particular importance to him in the original text. Personally, this text reminds me of the beginning of Goethe's FAust, where criticism of the conditions of Goethe's times and various public reactions are played on, and even the vinaigrette was already used there. Here, Nietzsche's text: 1. BAW I, P. 69 ff. (April, 1859) Fragezeichen und beigefügte Notizen, nebst einem allgemeinen Ausrufezeichen über drei Gedichte, betitelt Prometheus (Question Marks and attached Notes, in addition to a general Exclamation Mark with respect to three Poems, entitled Prometheus).It is always very unfortunate when a poet reviews his own works since one generally assumes that each poet turns a blind eye on his own weaknesses and, while, peculiarly, his other eye that is turned towards looking at the weaknesses of others, is the keenest eagle's eye. However, since it this is very common and well-known and since many books have already been written about the necessity of self-reflection, I have considered it to be not without merit to make a good start in it (meaning in the examination of my own errors). Already here, many will probably set an exclamation mark that is an indication of their agitation.-- The title of the poems in question is: Prometheus. Whew! General disgust. It appears as if the era of Aeschylus is supposed to be revived. Well, are there no human beings left so that one has to make titans reappear? (Slight doubts.) What an outrageous insult to today's humanity! Now, that everything is flourishing, we are supposed to return to the very fist beginnings of culture?--Is that not an inconceivable impertinence? (Here, the poet is shrugging his shoulders and clearing his throat from an artificial cough and saying: Most highly esteemed audience! I am pleased that I have the honor, the honor which, however, is bestowed on many and for which I, for many years, have craved like a deer craves for water, namely the honor to meet you, the all-perceiving and trend-setting public, an event which I, by the way, on the occasion if this, my first literary attempt, barely had the courage, the courage that still is inexplicable to me even now, and that has cost me many sighs and tears, the courage to step into the light with this weak product of my muse, in order to plead in the appropriate manner for its favor, upon which depends so incredibly much so that, in the event that this favor is not bestowed upon this your talent respectively genius, he is, to say it with a few words, he is lacking everything, and he is forced to return from his glorious hopes that filled his soul and that are, by the way, usually the product of his day dreams, into a nothing. Audience Fie, how unbearable to our distinguished, judging art critics' ears. Young friend, your prologue has to be criticized more than your work, itself. How stiff and forced, how bare of all poetry, what an unbearably long sentence! My tender nerves are unpleasantly touched by such ear-shattering words. How different would the following address sound: "It was on a heavenly beautiful day in May. The larks were singing in the ever-clear, blue skies, butterflies were hovering around the rose-bushes like playful elves. The mild, enchanting air that was filled with many fragrances, was enveloping me, and a never-before felt bliss filled my innermost. What emerged from my mind under these conditions, I now lay down in your temple, you muses, as a symbol of my gratitude, however weak it may be, you muses who have bestowed your favor upon me, and if a poor mortal may dare to ask for a favor from the heavenly ones, it would be that you might continue to bestow your favor upon me. May the eternal harmonies of poetry continue to sound in my mind's inner ears and transport it out of wretched everyday conditions into your blessed halls (the audience is weeping; the poet--? A fat captain: Can't you tell me what kind of animal Prometheus was? A young officer: A titan, Captain! The former: What is a titan? An old lady: Fie, sir, who wants to deal with such pagan stuff? Captain: Pooh...and even write poems about it! A Councillor: "No power can touch those who dwell on Mount Olympus' lofty top!" A Prof Does not our Aeschylus say here, that this is nonsense? Fat Captain: My learned student, who is Aeschylus, anyway? Student: A hero of tragedy, sublime in drama and action, achieving powerful effects with titans. The Former: With titans? Curious, a good gambler (having perceived the German word "Spiel" not as drama but as "Play" in the sense of "Game") and merchant (having perceived the German word "Handlung" not as action but as "business dealings") who can achieve effects in and with his novels? Is he still alive? The Latter: He lived a few centuries before Christ. The Former: Well, then Jean Paul must have lived at that time, too? (referring to the romantic writer Jean Paul (Friedrich Richter) and his novel, "Der Titan"). Prof Councillor: What does the young poet mean by "eternal"? Poet: Dear sir and patron, your kindness and extreme benevolence towards me totally confuses me (general laughter: ha, ha, ha) and I do not deserve, at all, that you are so concerned with me. (All have a serious look on their faces). It was on a beautiful afternoon on a day in May, the mocking birds were singing like organ pipes and it was raining down heavily on the rose bushes. I fled into your closed-in gazebo and there I laid down in your halls my books that were still wet from the pouring rain. (General hissing and noise) Then, the mocking birds began to chirp and the dogs began to sing-- excuse me, please- so -that the entire house was shaking. If it was ever granted to a mortal--(the noise is getting louder and louder) Prof Poet: In a state of trance, and with pathos. However, those heavenly forces will not be angry forever, Prof C Poet, with warmth

To you, unconsciousness appears to be a lovely way out St<udent>: Who do you mean by that, sir? P(oet): Do you feel yourself addressed? St(udent): I protest against such impertinence! An old lady: Oh, my nerves! These crude men! (Poet): St(upidity) has always been closely linked to weak nerves Lady: Stupidity, weak nerves, you are arrogant P(oet): No, that is too much for me, you are eccentric. Of(ficer). Sir, what do you mean? I would not have thought that! P(oet). That I have turned all of you into poets.  Prometheus-Drama / Chor der Menschen (partly quoted in the text) Since this satirical-(self)-critical text emerges quasi out of the blue amongst his other poems and dramas, this emergence appears to me to be the reason why H. J. Schmidt (and other "analysts") are trying to interpret a "meaning" into these poems and dramas that does normally not become apparent--this applies even more to the two following texts. Those who know how Nietzsche's thinking as a philosopher has developed will be able to recognize that already the Pforta student Nietzsche was moved by nearly all of those basic ideas that the philosopher would be concerned with, and that these ideas were already focused on more or less clearly--and this is certainly amazing in a seventeen-year-old ...

2. BAW II, 54 – 59 Early Works – April 1862 Fatum und Geschichte (Destiny and History). Gedanken (Thoughts).

[Mp II, 18, 1] Were we in a position to take a fresh, unbiased look at Christian teachings and at the history of Christianity, we might see ourselves forced to express opinions that are contrary to generally held views. However, since we have been under the yoke of custom and prejudice from early on, our minds' natural development and the formation of our temperaments has been stifled by childhood impressions, we almost believe that we have to consider it a transgression if we choose a more liberal position, in order to be able to form an impartial and timely opinion on religion and Christianity on its base. Such an attempt is not the work of a few weeks, but that of an entire lifetime. How could one destroy the authority of nearly two-thousand years, the testimony of the most ingenious men of all times, how could one lift oneself above all those troubles and blessings of the development of a religion that have left their deep impressions on world history, with fantasies and immature ideas? The desire to attempt to solve philosophical problems about which differences of opinion have been waged for several millennia is a truly an audacity, to topple views that, in the eyes of some of the most ingenious men, have elevated man to his status as a true human being, to attempt to unite science and philosophy, without even knowing the main results of either one, to ultimately postulate a system of reality that is based on science and history, while the unity of world history and the most basic principles have not been revealed to the human mind, yet. To dare to venture out into the sea of doubt, without a compass and without a guide, is foolishness and the demise of undeveloped minds; most will be crushed by storms, and only few will discover new territories. Out of the midst of a vast ocean of ideas one then longs for dry land: how often was I, in fruitless speculations, not overcome by the longing for history! and for science! History and science, those wonderful treasures of our entire past, the prophets of our future, they alone are the secure bases on which we can build our towers of speculation. How often did not all of existing philosophy appear as a veritable tower of Babylon to me; to reach high up into the sky, that is the aim of all great endeavors; heaven on earth would almost be its equal. An endless confusion, in the minds of the people is the result; there will still be many upheavals before the masses finally will have understood that the entire Christianity is based on assumptions; the existence of God, immortality, the authority of the Bible, inspiration and other issues will always remain problems. I have tried to deny everything: oh, it is easy to tear down, but rebuilding! And even tearing down appears easier than it is; through childhood impressions, the influence of our parents, our upbringing, our innermost has been molded in such a way that it is not easy to tear out those prejudices by means of reasoning or sheer will power. The power of tradition, the need for something higher, the breaking-off with all existing traditions, the dissolution of all forms of society, the doubt, if mankind has not already been misguided by a chimera, the sense of one's own audacity and daring: all of this wrestles with each other in a terrible struggle until ultimately, painful experiences, sad events, lead our hearts back to our old childhood faith. However, the observation of the impression of such doubts created in one's mind, has to be a contribution to one's own cultural history. It is not conceivable in any other way than that something remains behind, a result of all that speculation that might not always be knowledge, but also a belief, nay, even what, sometimes, stimulates or suppresses a moral feeling. As much as custom is a product of an era, of a nation, of a way of thinking, as much, morality is a product of general human development. It is the sum of all truths for our world; it is possible that it will not mean more in the infinite world than the product of a way of thinking does in our world; it is possible that , in turn, a universal truth will develop out of the products of truth of particular worlds! We barely know if mankind, itself, is not merely a level, an episode, in the overall scheme, in the development, if it is not a deliberate phenomenon of God. Is not man, perhaps, only the development of the stone through the medium of the plant, the animal? Would not, already, in this, perfection or fulfillment have been reached and would not in this lie history, too? Will this constant development never have an end? What are the power sources of this great clock-work? They are hidden, however, they are the same in the great clock we call history. The face of the clock can be compared to the events. The big hand on the clock moves on, hour by hour, in order to begin its journey anew after it has reached the number twelve; a new world era begins. And could one not consider immanent humanity to be that power source? (With this, both views would be united.) Or are higher considerations and schemes controlling everything? Is man only a means or is he the purpose? To us, he is the purpose, for us, there is change, for us, there are eras and epochs. After all, how could we recognize higher considerations or schemes. We only see how ideas are formed out of the same force, from humanity, under external impressions, how these take on form and life, how they become the property of all their conscience, their sense of duty; how the continuing development and production forms new material from it, how they shape life, how they govern history, how they feed each other (even) in their struggle and how, out of this mixture, new developments emerge. A variety of streams, struggling with each other, in ebb and tide, all moving towards the eternal ocean. Everything moves in ever-increasing circles around each other: man is one of the inner circles. If he wants to measure the vibrations of the outer circles, then he has to reflect and consider the circles around him and move thus, step by step, towards the outermost circle. The circles next to him are the histories of nations, societies, and mankind. It is the task of science to find the common center of all vibrations, the infinitely small circle; how, that man is searching for this center within himself and for himself at the same time, we realize what singular importance history and science have to hold for us. Since man is drawn into the circles of world history, a struggle between the individual will and collective will arises; this points towards that infinitely important problem, namely the question of the justification of the individual in the framework of his nation, the justification of nations within the framework of mankind, the justification of mankind within the world; in this also lies the basic relationship of destiny and history. Man is not in a position to grasp the highest concept of universal history; however, the great historian as well as the great philosopher become prophets, since both reflect upon and consider the relationships of all circles, from the innermost to the outermost. The position of destiny, however, is not secured, yet; let us take a look at human life in order to recognize some individual justifications and thereby also some overall justifications. What determines happiness in our lives? Do we owe it to the events into the whirlwind of which we are swept? Or does not, rather, our temperament lend its color to all events? Does not everything appear to us in the reflection of our own personalities? And do the vents not, so to say, only set the stage for our fate, while the strength and weakness with which they affect us actually depends on our own temperaments? Emerson recommends that we consult ingenious physicians, as to how much is not decided by temperament and how much is, basically, decided by it. However, our temperaments are nothing else but our mental states on which our circumstances and events have left their impressions. What is it that draws the souls of so many men with all might down to the low and commonplace and that prevents the flight of their ideas into higher regions? A fatalistic construction of their skulls and gone structures, the station in life of their parents, their everyday conditions, the commonplace atmosphere of their surroundings, even the monotony of their homelands. We have been influenced without carrying within ourselves the strength to develop an antidote (to this influence), without realizing that we have been influenced. It is a painful feeling to give up one's independence in the process of an unconscious acceptance of outer impressions, to have the capabilities of one's own soul crushed by the power of custom and traditions, and to have engraved into one's soul, against one's own will, the roots of confusion. At a larger scale, we find all of this again in the histories of nations. Many nations that have been confronted by the same events have, after all, been influenced in very different ways. Therefore, it is small-minded if one wants to impose on all of mankind one form of state, government or society, quasi in stereotypical form, all social and communist ideas suffer from this misconception. Man is, after all, never the same everywhere; however, as soon as it would be possible to overthrow the entire past of the world by means of a strong will, we would immediately join the ranks of independent Gods, and world history would mean nothing else to us but a dreamlike state of being lost in reverie; the curtain falls, and man finds himself, like a child, playing with worlds, like a child that awakens at dawn and wipes away all nightmares with a smile. Free will appears as that which is not chained, as that which is deliberate; it is the infinitely free, roaming, the mind. Destiny, however, is a necessity if we do not want to believe that world history is made up of dream-like meanderings, that the unspeakable pain of humanity is a fidget of imagination, the we, ourselves, are the powerless objects of our own fantasies. Destiny is the infinite force of resistance against free will, free will without destiny is as inconceivable as mind without real good or evil, since, after all, a certain quality or trait is always the product of contrasts. Time and again, destiny preaches the principle: "The events are what determine events!" If that were the only true principle, man would be the object of dark forces, not responsible for his own mistakes, entirely free from moral distinctions, a necessary link in a chain. Man is happy when he does not realize his own situation, when he does not convulsively jerk his chains, when he does not, in insane lust and desire, want to confuse the world and its mechanisms! Perhaps, free will is nothing but the highest potential of destiny, in a similar manner as mind can only be the most infinitely small substance, as good can only be the most subtle development of evil. If we consider the word world history in the most encompassing way, then it would (have to be considered) the history of matter. After all, there still have to exist higher principles in the face of which all differences have to flow together into a great unity, prior to which everything is in development, where everything flows towards a gigantic ocean, where all developments of the world find themselves again, united, merged, all one.– 3. BAW II, 60 – 63 Jugendschriften (Early Writings) – April 1862Willensfreiheit und Fatum (Freedom of Will and Destiny). [Mp II, 19, 1] Freedom of will, in itself nothing else but freedom of thought, is limited in a similar manner as freedom of thought is. Thought can not reach beyond the outermost boundaries of a circle of ideas, a circle of ideas, however, rests upon insights one has gained and can grow with their expansion and can be intensified, without, however, reaching beyond the limitations that are set by the construction of the (individual thinker's) brain. Similarly, up to the same point, freedom of will is capable of development and intensification. A different matter is the capability of practically applying will, of putting it to work; this capability is allotted to us in a fatalistic manner. In that destiny appears to man through the mirror of his own personality, individual free will and individual destiny are mutual adversaries. We find that those nations that believe in destiny excel in strength and will power, contrary to which women and men who let events take their course on the basis of Christian misconceptions based in the premise that "God has made all things well", allow themselves to be guided by circumstances in a demeaning way. Generally, "submission to God's will" and "humility" are often nothing more than excuses for cowardly fear of boldly facing destiny. If, however, destiny still appears more powerful than free will, then we must not forget two things, first, that destiny is only an abstract concept, a force without a material basis, that, for the individual, there is only an individual destiny, that destiny is nothing but a chain of events, that man, as soon as he acts, and thereby creates his own events, determines his own destiny, that, in general, events, as they impact upon man, must have, consciously or unconsciously, been caused by man, himself and that they must suit man. However, man's activity does not begin as late as with his birth, but rather already in his embryonic state and, perhaps, who can decide--already in his parents and grandparents. All of you who believe in the immortality of the soul also have to believe in the pre-existence of the soul, you have to also believe in this state of the soul's existence, if you do not want something immortal to develop out of something mortal, if you don't want to have the soul flutter around in the air until it is finally forced into the human body. The Hindu says: destiny is nothing else but the deeds that we have done in a previous state of our existence. On what basis is one supposed to disprove that one has not already acted consciously since eternity? On the basis of the entirely undeveloped consciousness and awareness of the child? Could we not, rather, say that our actions are always proportionate to our awareness? Emerson, too, says:

Mit dem Ding, das als sein Ausdruck erscheint (with the thing that appears as its expression). In any event, can a sound touch us if there is no appropriate chord in us? Or, to express it differently: Can our brain receive an impression if our brain does not have the receptive capability for it? Free will is also only an abstract concept and means the capability/ability to act consciously, while, by destiny, we refer to the principle that guides us in our conscious acting. Acting as such always also expresses an activity of the soul, a direction of the will that we, ourselves, do not have to focus on as an object. In our conscious actions, we can, as much as in our unconscious actions, allow ourselves to be guided by impressions, but also as little as in that case. In the event of a very fortunate action, we say: 'I have arranged it like that by accident.' That does not always have to be true, at all. The activity of the soul carries on, and that undiminished, even if we do not focus on it without mental perception. Likewise, we often believe that, when we close our eyes in bright sunlight, for us, the sun is not shining. Yet, its effect on us, the invigorating force of its light, its mild warmth, do not stop, even if we do not perceive it with our senses. When we, thus, do not perceive the concept of acting unconsciously as a mere allowing oneself to be guided by prior impressions, then for us, the strict division between destiny and free will vanishes and both concepts merge into the idea of individuality. The further thins are removed from the inorganic, and the more that education increases, the more distinctly does individuality emerge, the more varied are its qualities. Self-acting, inner force and outer impressions, their developmental levers, what else are they but freedom of will and destiny? In freedom of will, there lies for the individual the principle of separation, of separation from the whole, of the absolute freedom from limits and boundaries; destiny, in turn, organically reconnects man with the overall development and forces him, b seeking to dominate him, to freely develop his own strength against it; absolute free will without destiny would turn man into God, and the fatalistic principle would turn him into an automaton. [Mp II, 20, 1] Only a Christian outlook is capable of bringing forth such world weariness, a fatalistic outlook would not be removed from it any farther than it is. It is nothing but despair over one's own strength and power, a pretext of weakness, if one creates one's own destiny with determination. Once we realize that we only have to answer to ourselves, that an allegation of a failed destiny can only be addressed at ourselves, not at some higher power, only then will the basic ideas of Christianity take off their outer garments and move into our bloodstreams. In essence, Christianity is a matter of the hart, only when it has become embodied in us, when it has become the core of our hear and soul, will humans be true Christians. The main teachings of Christianity only convey the basic truths of the human heart; they are symbols, as the highest has to be the symbol of the even higher. Finding one's salvation through faith does not mean anything but the truth that only the heart, not knowledge, can make us happy. that God has become man only points towards the idea that man should not seek his salvation in the infinite, but rather create his heaven on earth; the delusion of a supernatural world has moved human mind into a wrong position towards the earthly world: it was the product of a childhood of nations. The glowing soul of man's youth accepted these ideas with enthusiasm and, forebodingly, reveals the secret that has its roots in the past and in the future, at the same time, that God has become man. Under desperate doubts and struggles, humanity matures into manhood: in itself, it recognizes "the beginning, the center, the end of religion." Live heartily well! Your Fritz SNmA. [Semper Nostra manet Amicitia] Pforta, April 27, 1862. This last section, which is the fragment of a letter to W.

Pinder and G. Krug (HKGA Briefe Vol. I, p. 180 ff.), which the editors of

the BAW placed directly after "Freedom of Will and Destiny", makes

clear that in the meantime, Nietzsche had received and read his Feuerbach that

he had wished for his preceding birthday (see

the Nuremberg Page) -- his inaccurate quote from Feuerbach's "Wesen des Christentums"

in quotation marks demonstrates his reference to Feuerbach; after all, at

the end of part 1 of this work, Feuerbach wrote: "Der Mensch ist der Anfang der Religion, der Mensch ist der Mittelpunkt der Religion, der Mensch ist das Ende der

Religion" (man is the beginning of religion, man is the center of religion,

man is the end of religion). (L. Feuerbach, GW, Vol. 5, p. 315)

With this, all arguments that one can still hear today over whether or not and

when Nietzsche had read Feuerbach, should be laid to rest. Peculiarly, at the same time, Nietzsche was capable of

writing to his mother (HKGA Briefe I, 183): "...we will not be able to see

each other, since I am going to communion at that time. For that, dear

Mama, wish me God's blessing!" How can this course of acting and writing be

reconciled with the contrary views of the Pforta Alumnus? However, in this letter to Raimund Granier, which Nietzsche

had written during his so-called "Hundsferien" vacation at Gorenzen,

one can note further details (HKGA I, 193): How one Becomes a Poet – On "Germania" and Nietzsche's awakening Self-Confidence

In the fall of 1862--probably in connection with his 18th birthday--another restrospective was due; on this occasion, Nietzsche compiled lists of his works, again, as before, for the Germania that he had founded with Wilhelm Pinder and Gustav Krug in the fall of 1860; what is peculiar is that, from May - September 1862, Nietzsche was the only contributor who submitted contributions as set out in the club's statutes, what, thus, meant the end of this association--due to attendance of different schools, but also due to Nietzsche's special status, the three had become estranged, and Nietzsche was not quite innocent in this. During this period, he was working on the text and music to his Ermanarich topic (a saga from the time of the Great Migration; later at Pforta, he would write his first review on it that he would continue to consider worthy of being read.) BAW II, 119 f. (October 1862) I am asking in advance that my review of my own poems will not be interpreted as an attempt at vainglory and self-indulgence. I am too far removed from the times in which I attempted to present myself with their effects, in order for me to (still) write self-congratulatory critiques. To the contrary, I do not intend to show what it is like to be a poet, what it is like to be born as a poet, but rather how one becomes a poet, that is to say, how, out of a diligent writer of poems, with increasing intellectual capabilities, one can, at least to some extent, also become somewhat of a poet. This as an introductory remark. It is not only interesting but rather necessary to recall in one's mind one's own past, particularly one's childhood, as faithfully as possible, since we can never arrive at a clear judgment of ourselves if we do not carefully observe the conditions in which we were raised and if we do not carefully continue consider the influences that were exercised upon us. To what great extent my life during my first years in a quiet pastor's home, the change from great happiness to great unhappiness and misfortune, leaving one's own village and the various events of city life, influenced me, I am still feeling the effects of which, today. Serious, easily swayed to move from one extreme to another, I'd say, passionately serious, in a variety of conditions, in grief and in joy, event at play [here, the text breaks off.] What do those lines teach us? In the first paragraph, a certain "poetic self-confidence" can be discerned--we shall become aware of it, soon, in connection with Nietzsche's criticism of his friends Pinder and Krug, in quite a different manner; however, Nietzsche's attempts at reflection are not not only limited to external events (experiences of his youth and to their effects on him), but rather, now he already includes self-formation. That his youthful self-confidence is somewhat hasty and premature, he comes to realize himself, a few years later--he stages (although not a very thorough) autodafe of his words and subsequently deals with hte requirements of his writing style in quite a different manner. He also loses his reigns in this attempt, he moves into a further attempt at spinning a thread out of his personal existence in connection with childhood events, into a web of reflecting self-observation--and breaks ff for the time being. However, he remains committed to working on himself, he is reflecting on the views that he is forming and that are doing so due to his own (literary) work (on the Nibelung saga, in connection with Ermanarich) as well as due to the material discussed in the Pforta curriculum (Livius, Horace, Homer). One can already find traces in those notes that would later be coined a "tragic world view", including the "morality" that is necessarily connected with it: Only profound, deep natures can completely sccumb to a terrible passion to such a degree that they almost appear to be stepping outside of humanity; what I abhor, however, is the heartlessness of those who can lift up the first stone against such unfortunate ones (Oct. 23, 1862, BAW II, 134) One can not avoid gaining the impression that, one the one hand, Nietzsche's self-searching reflections and the dissolution of his hitherto existing focal points (his social constraints and Christian constraints) are moving towards culmination. Obviously he has to--while he was entering the "Prima" as "primus" (valedictorian), blow off some steam: Above all, he needs "money, a lot of money", he plays "billiards, that amuses me", he attends "Thee dans ... You know who I want to see invited." (HKGA I, 199) And in his letter of November 10, 1862, (HKGA I, 200) he even dares--or does he just not know how to proceed?--to address his mother ans sister as "dear folks"--for which his mother will admonish him, and she has a further reason to be worried about her son, since he also acts up at Pforta. In quick succession, he becomes guilty of two "serious" offences: The first is related to a rather hilarious event, since it

shows, once more, Nietzsche's satirical side. As "Primaner", he

is appointed as "weekly inspector" by the "Hebdomadar"

(supervising teacher of the week), and his task is to "note everything that

requires repair in the quarters, the cupboards, armoires, in the auditoriums,

etc., and to submit it in writing to the inspection office." Since

this seemed to him to be a rather boring job, he rendered "all remarks in

form of a joke" in order to "spice it up with humor" (HKGA Briefe

I, 200). Nietzsche's sister preserved some examples that should not be

missed: In private, the consequences that Nietzsche drew from this were much more radical; for himself, he generalized the event into a matter of principle: Nothing would be more wrong than to show any remorse over that which has passed, accept it as it is. One should learn lessons from it but go on living calmly and one should observe oneself as a phenomenon whose various individual traits form a whole. Towards others, one should be tolerant and, at the most, pity them, but never become angry at them one should (also not) become enthusiastic about someone, they are all there for us, to serve our purpose. He who knows best how to rule will also be the best judge of character. Every necessary deed is justified, every deed necessary that is useful. Immoral is that deed that is, not being necessary, causing someone else distress; we, ourselves, are very dependent on public opinion as soon as we feel remorse and despair over ourselves. In the event that an immoral act becomes necessary, then it is moral to us. All actions can only be the consequences of our driving forces, without reason, of our reason without our driving forces behind it, and of our reason and our driving forces, at the same time" (BAW II, 143). Already in this, at first sight actually harmless event, one can observe the intertwining in Nietzsche of life and thought; already in his reflection on what his position should be in this, the 18-year-0ld creates for himself the platform of "beyond good and evil" from which he, unmoved, reduces life to the driving forces in the individual and elevates the individual's striving for power to necessity--even the plight of others is not only accepted as necessary, as long as it is, from the individual's viewpoint, "useful" and therefore necessary. Certainly, the youth Nietzsche did not want to advocate a mere subjective utilitarianism with it--however, when he later (at first) has to feel right at home with Schopenhauer's belief in genius, it becomes clear: That individual that "can rule best" creates his/her own morality. This raises the question how such self-conscience and confidence can be possible that differs in its path and in its aims very much from 'normality". As far as I can see, two different patterns are applied in explaining this: a) The one side goes out from a disposition of the "genius", combined with above-average ambition; what will, naturally, remain blurred and unclear what is actually meant by "genius"--this might very likely refer to "above average". Even more problematic is the clearer definition of this "inclination" that is described as being above average. Insofar, it is then mostly referred to as a combination of artistic and of thinking capabilities, musicality and poetic/language elements that are combined and contrasted with rationality, which is ultimately considered to be acting in their service. In the result (of this evaluation), the results of thought processes are valued less, while one gladly respects Nietzsche's superiority in aesthetic matters. No biographer fails to mention Nietzsche's too great ambition--in this, they only too gladly follow the older Rohde who can obviously not explain the "different nature" of his friend of earlier years, in any other way. b) Another viewpoint that Nietzsche, the psychologist, has conjured up, himself and that is still flourishing today, takes the opposite approach, that is, basically behavioristic: Nietzsche's development is seen as a reaction to his childhood experiences and to his environment. IN this, one refers to the situation of his upbringing in a pastor's house, to his father's death (and to that of his brother) and to the resulting family situation (Nietzsche, mainly surrounded by female relatives). Particularly "modern" is it (still and again) to probe Nietzsche's sexuality in Freudian manner and to draw conclusions from it to his development, although Freud's extreme premises have already been declared as being absurd. Thus, Nietzsche is accused of incest with his sister, of abnormal masturbation or respectively of homo-eroticism, his texts and letters are examined carefully with respect to it, yet by not taking the trouble to check if such hypotheses actually fit into the framework of his life. In doing so, one is even more careless with respect to the question as to whether and as to how his sexuality is connected with his thinking and his work. Are the writings of Byron, Wilde, or Gide in any way influenced by their sexual orientation? All of these behavioristic patterns of explanation are based on the assumption that such an extraordinary self-conscience and self-confidence is a result of a self-preserving reaction to factual conditions and to personal struggles; in particular, the boy is supposed to have suffered from an "ecclesiogenic neurosis" (H. J. Schmidt), and his writing activity that he started at age ten is to be considered as an attempt of liberating himself. These different driving forces: aesthetic talent, driving ambition, Christian indoctrination, psychoanalytical hypotheses based on sexuality, are depending on the writer, combined according to his own preferences and thus lead to completely diverging images of Nietzsche. A further role plays, of course, his infection with syphilis--the effects of which some writers already see emerging in 1883 with Zarathustra, without taking into consideration that the health complains that were so typical for Nietzsche already emerged during his youth (and are certainly linked to a strong myopia) and on account of which he had to visit the sickroom at Pforta many times, without the reason for this having been found. These bouts of pain and suffering would ultimately lead Nietzsche to give up his Basle professorship. Extract of the notes concerning Nietzsche from the Sick Book (Admission Book) of the Pforta State School (left our are particulars such as age, body constitution, that is, throughout, referred to as strong, the listed data refers to the admission and release dates) [HKGA Briefe I, 340]:

However, let us return to the Pforta student and to his growing self-confidence; in April 1863, he wrote in the Poem "Jetzt und ehedem" (BAW II, 189 ff.): So schwer mein Herz, so trüb die Zeit Und hast es funden? Hin ist hin! After his last religious exaltation that was brought on by his confirmation in 1861, (together with Deussen who described this event), this break with traditions was probably brought on, in part, by his private and school activities connected with ancient/classical thinkers, but also, to a great extent, by his reading of Feuerbach's writings and his reflecting upon them, as it found expression in his "fatum" texts (featured above). He has cut himself loose and is on his way to finding himself; that he is also aware of this, shows the following lengthy extract from his criticism of Pinder in the context of the latter's submission to the Germania. It is no wonder that Nietzsche's friends, after such a barrage of criticism, were no longer in the mood to get scolded, any more. At the same time, this text also reaches far into the future, namely to Nietzsche's "First Untimely Observation" against David Strauss--obviously, Wagner did not have to entice Nietzsche that much to write it, since such form of criticism was apparently "in his blood", even if he was just becoming increasingly aware of it: He obviously enjoyed fencing! The Poetic Achievements of W. Pinder. To the Germania by the Chronicler 1862-63. FW Nietzsche After we have reviewed the musical products of our Germania,

we are turning to the poetic ones. Here, W. Pinder may do us the honors,

first. To translate an exercise from French into German and to turn German

prose into bad rhymes and verses--if that is an accomplishment, then is is a

small one, although the effort may have been far greater than the outcome.

In April, another translation of two poems from medieval High German appeared,

obviously, a very careless work, of which only the calligraphic

achievements--compared to the actual work--can be praised.... Also in his letters to his mother, one can really see his own personality emerging for the first time. Franziska Nietzsche had sent her daughter Elisabeth to a boarding situation in Dresden for her further social grooming. On the occasion of this, her son wrote to her (HKGA Briefe I, 177 f.): ...If she is only staying at a very distinguished boarding house! I can really not warm up to Dresden, it is not great enough, and in its peculiarities, also in its language, too close to Thuringian elements. Had she, for example, gone to Hanover, she would have become acquainted with completely different customs, peculiarities, and a different language; in order for a human being not to become too one-sided, it is always good if he/she is educated in various regions. Otherwise, as a city of the arts, as a small residence, and overall, Dresden will suffice for E<LISABETH'S> mind and I envy her to a certain extent. However, I have a premonition that I will be able to enjoy a great deal of that in my life. At present, I am eager to hear how ELISABETH is getting along in her new surroundings. A boarding house is always a risk. However, I have great confidence in ELISABETH. If she could only learn to write more prettily! Even when she is talking, she has to leave off these many "oh's" and "ah's" as in "oh, you can not believe how wonderful, how beautiful, how charming, etc. that was" and so many little things that she will hopefully forget when she is mingling in better company and with greater care and attention to herself. Two things appear to stand out here: Nietzsche argues from his own experience and judgment, what outer circumstances would be the right ones for the development of the mind, whereby he is going out from a certain "greatness"--he wants to "make something of himself", and this should also apply to his sister, and he certainly sees himself as the "big brother" Elisabeth who, in lieu of her father, is taking an interest in her development. Obviously, he had internalized the "bourgeois ideal" since that time. Although he should have been warned by the November 1862

events, it got even worse in April, 1863--guilt-ridden, he wrote to his mother (HKGA Briefe I, 209 f.): Decision in Favor of Philology Shortly after this, NIetzsche found himself in the sick room, again, due to a cold, and had an opportunity to think about his professional career (HKGA Briefe I, 213): As far as my future is concerned, those entirely practical

considerations are what concern me. The decision as to what I should study

does not make itself. I have to think about this, myself, and choose; and

it is this choice that is difficult for me. It is certainly my aim to

study that which I will choose, thoroughly, and all the more difficult becomes

my choice, since one has to choose a discipline in which one hopes to be able to

achieve something good. And how deceiving these hopes often are! How

easily does one allow oneself to be torn away from family tradition or from

particular wishes by a momentary preference, so that the choice of a profession

appears to be a lottery in which there are many losing tickets and only few

winning tickets. On top of it, I am in the particularly unpleasant

position to really have a great number of interests that are spread over various

disciplines, the satisfaction of all of which would turn me into a learned man,

but hardly into a professional of a particular discipline. That I,

therefore, have to disregard some interests, is clear to me. That I have

to gain a few new ones, as well. But what interests will be the

unfortunate ones that I will throw overboard, perhaps my very favorite

ones! It becomes clear that he did not see himself focused on theology, anymore, as it is requested of him by "all family tradition" and particularly by his mother, even into his Bonn year. At the end of September, 1863, he wrote: "One really lives a great deal in the future now and makes plans for one's university years: even my present studies are already geared towards that." For his upcoming birthday, he therefore requested "only scientific works", namely philological ones (HKGA Briefe I, 226). We find this decision confirmed by his most important writings (discussed here), both of which point into this direction, namely his treatise on the "Gestaltung der Sage vom Ostgothenkoenig Ermanarich bis in das 12te Jahrhundert" of October 1863 (BAW II, 281-312), and, to an even greater extent, his work on the Chorus in Ödipus Rex of April 1864 (BAW II, 364-397), which consists of a Latin introduction and of three partially ancient Greek, partially Latin, partially German comments. In it, we can already find a premonition of basic ideas expressed in his (later) "Geburt der Tragödie" (Birth of Tragedy), and, at that, already with hints at the "ingenious reform plans" of Wagner as the reformer of opera! Altera commentarii pars While the Germanic drama has developed out of the epos, out

of the epic tale of religious content, the ancient Greek drama had its origin in

lyricism, combined with musical elements. These beginnings explain a great

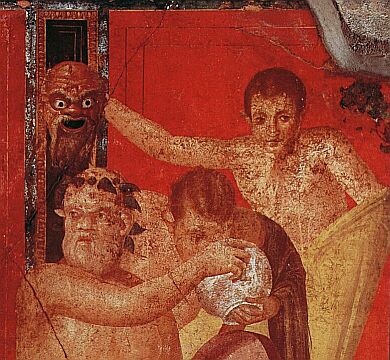

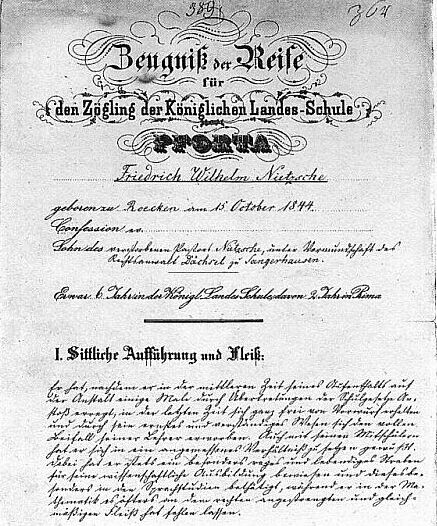

deal with respect to the history and peculiarity of both.  Pompeji, Villa dei Misteri Dionysos, the master of tragedy, distributes wine. In this work, Nietzsche not only already mentions Dionysus and his Dithyrambs, Dionysus who, as is known, is identical with Bacchus, but also his later counterpart, Apollo, already appears (S. 398): ... Thus Apollo is a God of sun and light, and, at the same time, the inventor and master of sounds.  New discovery in Pompeji: a fresko of Apollo Thus we can already see not only some of his basic concepts of his "tragedy" work of 1872, but also the main characters of this work. With this, it becomes clear that this work can not have been influenced by Wagner to such a high degree as some maintain. However, not only the first basic concepts, as we find them in Nietzsche's later works, appear, but also his own viewpoint that he later described so vividly, is also emerging, already, as, for example, in his text "Ueber Stimmungen" (about moods) (BAW II, 406-408) – who would not notice a certain similarity to his comments in his works? Fight is the constant nourishment of soul, and it would still know how to take out of it enough sweetness and beauty...it is probably true that each of these similar mood(s) represent progress to me and that it is unbearable to the mind, to go through the same stage that it has already gone through, once more; it wants to move ever more into depth and height. In June, 1864, it became clear to him that he would decide on (studying) philology--significantly enough, he did not announce this in a letter to his mother, but rather to his friends Gustav Krug and Wilhelm Pinder, who, in the meantime, had taken up their studies of law at the University of Heidelberg and who wanted him to join them there; however, he declined this, since he had already selected Bonn as his university, where the most prominent philological authorities of his time were lecturing, namely Jahn and Ritschl (HKGA Briefe I, 245) If you are interested in learning something about my present studies, then hear this: I am writing on a large work on THEOGNIS, and that by my free choice. Again, I have delved into a great deal of assumptions and fantasies, intend, however, to complete this work with as much philological thoroughness and as scientifically as possible. In the (so-called) "Hundsferien" school holidays in July, 1864, he completed his work on THEOGNIS, and in a letter of July 4, 1864 (HKGA Briefe, I, 250), he wrote his remarks on the "old ORTLEPP" that, today, are extensively interpreted and, in my humble opinion, over-emphasized. By the way, the old ORTLEPP is dead. Between Pforta and

Almrich, he fell into a ditch and broke his neck. In Pforta, he was buried

early in the morning, during dark, rainy weather; four workers carried the rough

coffin; Prof. KEIL followed with his umbrella. No clergy. That is all that we ever learn from Nietzsche with respect to Ortlepp; with the help of assumptions and hypotheses, one tries to present this formerly known political writer, poet and Byron translator as a "source of inspiration" and as the perhaps most important help in the development of the young Nietzsche. (H. J. Schmidt in Aufklärung und Kritik, Nietzsche-Sonderheft No. 4/2000, p. 87 ff. with further literature mentioned). It appears to be a known fact that Ortlepp, without employment and run-down, was staying around Naumburg and Pforta in the early 1860's and that he had contact with Profrta students, particularly in the inns near Pforta. It is obvious that not only Nietzsche himself but also Pinder knew of the existence of Ortlepp and that he must also have known him, otherwise Nietzsche would not have written to him about him. The simplest explanation for this "acquaintance" might be that even in those days, O. was still able to publish "great festive poems" twice a week in the Naumburger Kreisblatt which the three literary-minded friends would certainly have noticed. What would be more natural than for these Pforta students to set a tombstone for this poet who had formerly been known all across Germany and who, on top of it, cam from this region? Moreover: Nietzsche reports that they had raised "40 Thl."--a large sum at that time (for example, in Bonn, Nietzsche had to make do with 30 talers a month!); this means, however, that a great number of Pforta students had donated money and probably also the teachers, since this amount could not have been raised, otherwise. This puts the above-quoted mention by Nietzsche and the importance it is accorded by some writers in an appropriate context: He participated in according Ortlepp some last honors under these sad circumstances, as many, many others also did, and he wrote to Pinder about it, with whom he may very well have read the poems of O. Nietzsche's Pforta graduation paper, formerly a duty, during his days, however, voluntary, deals with the ancient Greek poet Theognis of Megara (BAW III, 21-64), who lived in the 6th century B.C.; the text is completely written in Latin, save, of course, many ancient-Greek quotes. In three parts, it deals with Theognis' life, the circumstances of that time at Megara, Theognis' songs as well as his views on the Gods, the customs and on the state. (Theognis lived in the time of transition from the monarchy to democracy, and as a representative of the first, he was sent into banishment.) The work ends: To God, FWNietzsche (on Sept. 7, 1864) With this, Nietzsche bade farewell and took his so-called "Mulus" vacation before he, after a trip to the Deussens in the company of his friend, went to Bonn to begin his studies. At the end of this section, let us take a look at his graduation certificate--on account of his weak performance in mathematics he alsmost was in danger of failing and had to undergo an oral examination (see also our Page on his Youth):  Nietzsche's Pforta Graduation Certificate I. Personal/Moral Conduct and Diligence. After he had contravened school regulations with several transgressions during the middle period of his stay, he kept himself completely clear of any complaints during the last period and, due to his serious and reasonable conduct, he has earned full approval by his teachers. Also with his fellow students, he was able to carry on pleasant relations. In doing so, he has displayed a particularly active and lively striving for his scientific training, particularly in language studies, while he often did not display a truly earnest and regular diligence in mathematics. II. Knowledge and Skills. (Chronik p. 108 f.) Nietzsche's First, "full-fledged" Poem At the end of Volume 2 of Nietzsche's Early Writings up to 1864, BAW, so-to-say as a transition piece of his changeover period from Pforta student to University student in Bonn, features an untitled poem by Nietzsche, of which it is difficult to decide if it, in the eyes of the writer, was completed or not, if one looks at the formally open ending without any punctuation. (BAW 2, 428 – Mp I 75) Noch einmal eh ich weiter ziehe Darauf erglühet tiefeingeschriebe<n> Ich will dich kenne<n> Unbekannter, This is his poem from the year 1864, which the BAW editor also featured in facsimile form (BAW 2, between p. 320/321)–to which one should note several things, both with respect to form and content. What is not clear, is the precise dating of this poem and its recipient, the comment that follows it (BAW 2, 457) is somewhat lapidary: "428: HS. 1 Quartblatt (16 X 20,5)." [Hs. = Handschrift]

What remains in question is as to whether the poem was really serving as a look back at Nietzsche's Pforta time; even though the first line of the poem ("eh ich weiter ziehe" "before I move on") would invite such an assumption, it does not prove anything, since, with this moving on could also be meant an inward and personal path that Nietzsche took – the overall content of the poem would speak for the latter. Further inaccuracies mentioned below lend weight to the argument that the editor's choice was rather nonchalant and subjective, also with respect to the dating of the piece and the "prominent" place it received at the end of volume 2 as well as at the end of Nietzsche's Pforta years. H. J. Schmidt discusses this "dem wohl meistzitierten Text des Schülers Nietzsche" (perhaps most often quoted text of the student Nietzsche), that even found entry "in christliche Gebetbücher" (into Christian devotional books), at great length (Nietzsche absconditus II/2, p. 618-645). "Das ‚erste vollkommene Gedicht Nietzsches‘, ‚das heute in die Weltliteratur eingegangen ist‘" (Nietzsche's first, complete poem, that has become part of world literature), does not only read "nicht nur auf den ersten Blick so unkonventionell fromm"(itself, af first sight, like a rather unconventionally pious text) and, with this, "eine Nagelprobe auf jedwedes Nietzschespurenlesen dar" (would provide a pivotal point of departure for any "Spurenlesen" [following of traces] of Nietzsche. Thus, already the theologian Jul. Köhler (Friedrich Nietzsche nach seiner Stellung zum Christentum, p. 16) featured this poem in 1902, in order to point out Nietzsche's "Hang zur religiösen Spekulation"(inclination towards religious speculation) who was supposed to have, "nicht ohne Schuld, Gott preisgegeben" (p. 31 "not without guilt, relinquished God") –from the beginning, Nietzsche had been claimed by the "Verteidigung des Christentums" (defense of Christianity", his "super human" was interpreted according to Christian terms, and even he, himself, was described as an "Erzieher zu Christus hin" (p.23, "educator towards Christ"). It could not be any more paraodx--however, in doing so, theology only continues its proven practice of exegesis out of the spirit of the "ecclesia triumphans", that already had proven successful in the interpretation of the Bible in comparison to the letter of the "sacred text", for centuries. To say it right at the beginning: Personally, I read

this text, and that in all three strophes, completely differently--I can not

detect any conventional piety in it, rather, its tone reminds me of Goethe

between Prometheus and Faust, far beyong any Christian devotional lyricism: Significant with respect to Nietzsche’s own opinion of his youthful, ‘Christian’ poems is a draft of a letter of his to his mother from October 1886, which he, “considerate” as ever, only sent off in a milder version.

Obviously, Franziska Nietzsche had praised him for one of his youthful poems. On October 26, 1886, he drafted the following reply: Let us first take a look at some formalities in comparing the

text printed by the BAW editor with the facsimile original:

"geblieben", "Schlingen", "niederziehen", "fliehen", "zwingen": in

all of these cases, we find almost identical indications of the

"en"-ending. Here, I want to point out two things: However, the editors view of the text appears to be covered by the first strophe: Only by omitting the "e" in "niederziehn" and "fliehn" do the respective verses of both strophes run perfectly parallel in form. Far more important – particularly with respect to the interpretation of the content – are three peculiarities that the editor 'quietly overlooked' in his text on p. 428, in comparison to the original:

1. Here, in the last verse of the first strophe, Nietzsche had, at first, obviously written "dein" and subsequently replaced the "d" by an "s", thus meaning "sein". This transition from the second to the third person that was (unintentionally?) not carried out in the fourth verse of this strophe, is important with respect to the interpretation (of the content), and that all the more, since in the second strophe, the address is again held in the third person, and in the third strophe, he returns to the "du" of the second person. If one further considers that the address of "du" achieves a much greater closeness than the address of "er" or "sein" of the third person, the result would appear to be a double-transition of perspectives throughout the poem. 2. In the third verse, after "ob ich" one finds something crossed out in "ihn", in the place of which the editor prints "in" without any comment. However, the line would indicate that not only the "h" was supposed to be crossed out but rather the entire word. This complete crossing-out of the "ihn"/"in" can be proven by pointing out that otherwise, the verse would have five iambic feet rather than four, in contrast to the equivalent verse of the first strophe and the overall concept of five iambic feet. 3. Most important appears to be the following: In the second verse of the second strophe, at first, Nietzsche suprisingly puts the word "Worte:" in brackets in order to write next to it "Gotte". What might that mean? First: He does not simply crosse out "Worte" (as with "ihn") in order to replace it with "Gotte"; this would mean that the setting in brackets of the word "Worte" would indicate that this word also carries some meaning that can not be foregone, even by putting it in brackets, and that it should be preserved in the overall context. The reason for the replacement might, at first, have merely been an external one, since otherwise, the verse would receive a rather ugly repetition: Darauf erglühet tiefeingeschrieben (Thereupon, written deeply inside, the word)

In this context, H.J. Schmidt

reminds us, not without justification, of the introduction to the Gospel of St.

John and its thoughts centering around "word" and God", what has

also been taken up by Goethe in Faust. In any event, a significant light is shed

on the question as to of what "God" Nietzsche could be writing

here--depending on what meaning a reader accords to this, the results might be

as differing as to achieve opposite results with respect to the surmised import

of the poem. With this, we have arrived at a discussion of the content of the poem, however, not from the viewpoint of how we would interpret it, but rather from Nietzsche's point-of-view, namely what he might have meant to express with it. For such an interpretation, various alternative paths offer themselves: – the Christian interpretation, assuming that Nietzsche might have had a 'relapse' into the religion of his father. – a 'Classical Greek-Pagan' interpretation; such as in St. Paul's context, when he found an altar in Athens that was dedicated to the "Unknown God", or related to one of the Greek deities, such as Zeus, Apollo, and Dionysus, that, for a long time, offered possibilities of identification to Nietzsche, as H.J. Schmidt also discusses them extensively; – from an inner connection, out of which man gives firth to religion and god, such as Nietzsche had read it in Feuerbach? (see above, "Destiny and Freedom of Will"). At first sight we can recognize that these three modes of interpretation are entirely incompatible--thus it would, at first, appear impossible that Nietzsche might have alternated between those possibilities; for this, the poem also appears too much as having been written in one and the same spirit and tone. If we first concentrate on this tone, we would have to contend that nothing would speak for an attitude of Christian humility being expressed with it: It is lonely Nietzsche, himself, who has solemnly consecrated the altars (strophe 1)--as a Christian, he would certainly not have grown lonely within his family and at Pforta, and of altars that had been consecrated by others, there were already enough. Thus, his altar is consecrated to the unknown God, as strophe 2 and 3 make clear--the consecration of the altar is a promise for the future: Nietzsche very likely seems to feel the (inner) working of this God--rather anonymously, while his concrete acquaintance with this God still lies in the future: "Du Unfaßbarer, mir Verwandter! Ich will dich kennen, selbst dir dienen" (Thou Unfathomable One, akin to me! I want to know Thee, and serve Thee). In the event that Nietzsche would have referred to the Christian God, with whom he was familiar from childhood on, such words would have been entirely out of place; if directed at the Christian God, they might even be considered blasphemy; and if directed at the ancient Greek Gods, with whom he dealt extensively with at Pforta in connection with Greek tragedy, they, in their own complexities, could certainly not serve him anymore, rather, they now only served him for the demonstration of partial identifications (as would later, in the "Birth", do Apollo and Dionysus). "Ich will" (I want), "selbst dienen" (to serve thee, myself), "mir Verwandter" (akin to me) --here, we can discern the self-confidence of man who recognizes "den Anfang, die Mitte, das Ende der Religion" (the beginning, the middle and the end of religion) in himself. What else do we learn besides the fact that the lonely Nietzsche consecrates altars from "the deepest bottom of his heart" to this unknown God, as a reminder and an obligation to himself? First, he attempts to call on this God in a very personal manner, however, since he does not know him yet, already in the first strophe, he switches to the third person in addressing him and thereby shows the distance that exists between him and this God, the reason for this still existing distance is described in the 2nd strophe: Here, he looks at himself and at his being entangled in wordly matters: "Sein bin ich, ob ich der FrevIer Rotte / Auch bis zur Stunde bin geblieben: / Sein bin ich – und ich fühl' die Schlingen, Die mich im Kampf darniederziehn / Und, mag ich fliehn, / Mich doch zu seinem Dienste zwingen. (I am his, even if I remained with the hord of the infidels. Up to this hour: I am his - and I feel the ties That pull me down in fight And, even if I should flee, Still would force me into his service.) It is particularly this part of the poem that would point towards a Christian interpretation: The contrast between a sinful here-and-now ("der Frevler Rotte" / the hord of the infidels) in which Nietzsche is still entangled and his "service" of a God whose sole property, whose "child" he wants to be, might, on the surface, have a Christian smell (how else should it have been with a child who grew up in a pastor's family who, from childhood on, was prepared to walk in his father's 'pastoral' footsteps?) It should also be clear that the crossed-out "ihn" is not necessary in order to fully understand the poem--the 'Dativus possesivus' accomplishes the same. The meaning depends on two things: What kind of "unknown God" is this (for whom Nietzsche also, obviously deliberately, did not cross out the attribute "word") – since from this, we would understand what "horde of infidels" we would have to imagine, which obviously appears to be a negative counterpart to this God. Or could it not also be the reverse? Could one, by drawing conclusions as to what Nietzsche might have meant by the "horde of infidels", not find clues as to what kind of "unknown God" he was referring to? Equally important is the peculiar reference to the "Schlingen" (ties) that drag him down in fight: Who do these belong to--to the God or to the "horde of infidels"? Although, up to this hour, Nietzsche could not free himself from this horde of infidels, yet, in reality, he is no longer at their side--as he writes in strophe 1, he is completely "vereinsamt" (lonely), and that obviously in the middle of this horde; and in spite of his apparently belonging to them, he knows that he belongs to his "God". Can that be the same Christian God to whom, quite obviously, this entire horde of infidels belongs, by which nothing else but his normal surroundings are meant, from his fellow students to his teachers, nay, even his own family--and from all of these, this lonely wanderer has cut himself loose (he, who already walked his own path for quite some time)? Very likely not. What is, thus, the "blasphemy" of all those "normal humans" that Nietzsche is surrounded by, and from whom he wants to cut himself loose by marching along his lonely path? What could those "Schlingen" (ties) tell us--due to their ambiguity, the last four verses of strophe 2 it is not quite clear, yet, that these are the ties of God that drag Nietzsche down and force him into his service, such as a Christian interpretation would or might suggest. Rather, it would be quite illogical that he should experience these ties, if they are supposed to be his God's ties, as "fight", as "dragging him down", as "forcing him", since he does not want anything else but to serve this God "himself" and towards whom he is striving in upward motion. Such a God, towards whom he is already moving, does not need any ties, and to flee his ties and to fight against them would mean that they would impede his progress towards this God. Therefore, these ties cannot be those of his God, rather, it are the ties of the "horde of infidels", and thus it immediately makes sense that these would "drag him down in fight", since it is not that easy to cut oneself loose from everything that one held dear from childhood on. That affords a fight, and sometimes even relapses, in which one despairs at one's own strength--"und mag ich fliehn": this flight only makes sense if it refers to his striving towards his "service" for his God; it would be completely illogical if he would want to flee the ties of his God. No, the ties are those of the "infidels" that want to hold on to him--and, giving in to them, he would actually flee from his God and from his own path, and the ties of the infidels are precisely that which want to force him to do the opposite of what he wants to do, "to serve him". Instead of tying him down, they repel him--the "doch" (yet) makes it abundantly clear: The Pforta graduate can no longer tolerate that his environment wants to "drag him down", and, at the end of his school years and on his way to his own studies, he no longer has to tolerate it: For a long time, he had to silently serve his "tiefeingeschriebenen Worte" "in tiefster Herzenstiefe" "vereinsamt" in secret--now, he leaves these ties behind, they offer him one more chance of freeing himself. "Ich will dich kennen Unbekannter, / Du tief in meine Seele Greifender, / Mein Leben wie ein Sturm durchschweifender / Du Unfaßbarer, mir Verwandter! /Ich will dich kennen, selbst dir dienen" (I want to know Thee, unknown One, / Thee, who is reaching deeply into my soul, Who is raging through my life like a storm Thou Unfathomable One, akin to me! I want to know Thee, and serve Thee) Later, he would describe this mood of departure with the image of Columbus that he would give to Lou Salomé as a farewell gift, and already the boy Nietzsche had written a 'Colombo' poem--Nietzsche moves on continually, as he already announced it in his youthful poems, and as he expresses it here, in the first line of this poem. What abut his arrival, the fulfillment of his wish, namely his wish to want to know his God? The self-deification of man, particularly as projection within the meaning of Feuerbach's thinking, was already known to Nietzsche; God and Man are (more than) "relatives"! However, as with Feuerbach, with Nietzsche, too, there remains an obviously indissoluble "religious rest" that both aim at re-claiming for immanence, from transcendence: What is the "unfathomable" that reaches "deeply" into the soul, that actually lends Nietzsche's life its vitality, that "rages through his life like a storm"? Does this poem, with this master of punctuation, which Nietzsche proved to be, very early, remain totally open, without any period, any hyphen, any exclamation mark or question mark, that he otherwise knows precisely how to apply? Or is the poem not complete, a fragment? Obviously, the editor was of this opinion, since he prints at the end of the poem: (Fortsetzung nicht vorhanden.{the end has not been preserved or does not exist]) and, in doing so, shows his incompetence with respect to this poem also here. Superficially, one could argue in favor of the poem being incomplete: First, on the basis of the missing final punctuation, second, on the basis of the fact that the last strophe, in contrast to the the first and second strophe, only has five verses. Formally, against this superficial perspective also speaks the cohesiveness of the third strophe, if one goes out from the five verse beginnings that are also vocally intertwined: "Ich" (I)– "Du"(You) – "Mein"(Mine) – "Du" (You) – "Ich" (I). Such a deliverate arrangement speaks for completeness, since nothing can follow here, any more. The same holds also true with respect to the content: Everything that Nietzsche wanted to say and was able to say at that stage in his mental journey was expressed– now, it is moving on towards the unknown God, his presence is already announced by the storm that takes hold of the soul, however, the rationally expressible self-identification with that which is, for the time being, recognized as being "akin" but still unfathomable, can only occur in the future – "Ich will dich kennen, selbst dir dienen" (I want to know thee, serve thee, myself). No punctuation would have been

able to provide a conventionally adequate "conclusion" to this

venturing into new territory, there, where everything remains open and

unknown. This circumstance is emphasized by the exclamation mark of the

second-last line: After all, it was not as if Nietzsche did not have the

appropriate punctuation marks at his disposal--it would have been easy to him to

also conclude the last line with one, two or even three exclamation marks.

However, in contrast to the second-last line, in which Nietzsche went out from a

present personal experience, in which his inner relationship to his God had

become clear, which lends strength to his own conviction of being on the right

path--what he, therefore, can rightfully exclaim!--in the last line, the

unfathomable and incredible of the path that is lying before him, becomes clear

to him in a real sense. Therefore, for Nietzsche, there is, perhaps, in

this situation, no possibility of ending this line with a punctuation mark, himself. From his Bonn Year (Oct. 1864-Aug. 1865) Entitled "Mein Leben", Nietzsche wrote another review of the events in his life. At this point, his reflections were very likely spurned on by his switch from Pforta to the University at Bonn. You can read this text in its entirety on our Page on His Youth. In it, Nietzsche expressed a self-confidence based on having found himself, and which mainly concentrated on himself, putting a distance between himself and the world around him. This becomes clear for the first time in his almost peculiar position towards his family (BAW 3, 66 ff.): Of the earliest period in my childhood I know little; what has been related to me about it, I do not like to repeat. I certainly had excellent parents, and I am convinced that particularly the death of such an outstanding father, as it, on the one hand, deprived me of fatherly support and guidance for my later life, and, on the other hand, sowed the seeds of the serious, reflective in my soul. If we recall his earlier delight in relating his experiences, as for example, in his reminiscences in "mein Leben" of 1858, then [we will realize that] this reluctance and aloofness stands in sharp contrast to it. With respect to his parents and particularly with respect to his father, he now shows a two-fold mental reservation, as it finds expression in his use of words like "certainly" and "I am convinced". It appears to me that, on the one hand, he is keeping a distance to his family and his experiences connected with them while he, in doing so, on the other hand, is standing on his own feet in order to keep his father's profession at bay. At least, it appears to be an ambiguous and two-faced statement that, under the cloak of a grateful son, bids farewell to his childhood and its dependencies in serious self-reflection. And thus he was able to freely express his own preferences, namely a view of life based on ancient-Greek values and in connection with it philology. Something that he still loved at this time, he later felt that he had to tear out of his heart: At the same time, my inclination towards classical studies grew; with fondest memories, I recall my first impressions of Sophocles, of Aeschylus, of Plato, particularly in my favorite work [of his], the Symposium, and then, of the ancient Greek lyricists. Plato and his Symposium as favorite work – who would have thought that in light of his later condemnation of everything Socratean and Platonic? This shows us that, at this time, he was by far not as critical towards the reflection of reason as he (would be) later, as, for example, in his "Die Philosophie im tragischen Zeitalter der Griechen" (KSA 801 ff.; by the way, a key text for getting acquainted with Nietzsche's position towards the ancient Greeks). Rather, he forewaw for himself an academic life/career, quite Goethean, did he want to limit his interests to avoid becoming to shallow in keeping this range too broad, and often, he emphasizes the importance of method--without, however, concretely enlightening us with respect to it wherein he has found this method for himself, in philology. One can certainly attribute his objective striving for science and psychology, up to Menschliches – Allzumenschliches to this aspect of his nature. In this state of striving for increasing deepening of

knowledge I still find myself now, and it is natural that, most of the time, I

think as little of my own achievement as I also do about those of others, since,

of every subject, I find that it can not be profoundly grasped or that it

is at least difficult to do so. ... Now that I am about to enter

university, I consider the following principles as necessary to strictly adher

to: to fight against any inclinations towards acquiring knowledge on a

broad and shallow base, and to foster my inclination to trace everything back to

its deepest and widest base. If those inclinations do not appear to cancel

each other out, then this is certainly not untrue in certain instances, and here

and there, I notice something similar in myself. In mid-October, we find Nietzsche in Bonn, where he has

rented lodgings in the Bonngasse 518, at the corner of Gudenauergasse; at once,

as still often during this time, he wrote home for money, he could not even

enroll without it. He also needed a "Pauper's Certificate" in

order to apply for scholarships respectively to allow for deferred payment of

his tuition fees--it can easily be imagined that for someone who wanted to

appears as belonging to the upper boureoisie, these circumstances were hurting

his self-confidence. The other one, Nietzsche, is a profound and thoughtful nature, inclined towards philosophy, particularly that of Plato, in which he is already engrossed to a great deal. He still appears to be wavering between theology and philosophy, however, the latter will win, and under your guidance, he will fondly turn to philosophy towards which his innermost striving directs him. In his aiming at socially "belonging", he teamed up

with Deussen and other Pforta alumni and joined the "Frankonia"

fraternity; the many evenings spent at pubs and the many excursions and outings

he took part in did, naturally, not have a positive effect on his cash flow nor

on his studies--in the first semester, he still enrolled in theology!--let